Page Not Found

Page not found. Your pixels are in another canvas.

A list of all the posts and pages found on the site. For you robots out there is an XML version available for digesting as well.

Page not found. Your pixels are in another canvas.

This is a page not in th emain menu

Published:

This post will show up by default. To disable scheduling of future posts, edit config.yml and set future: false.

Published:

This is a sample blog post. Lorem ipsum I can’t remember the rest of lorem ipsum and don’t have an internet connection right now. Testing testing testing this blog post. Blog posts are cool.

Published:

This is a sample blog post. Lorem ipsum I can’t remember the rest of lorem ipsum and don’t have an internet connection right now. Testing testing testing this blog post. Blog posts are cool.

Published:

This is a sample blog post. Lorem ipsum I can’t remember the rest of lorem ipsum and don’t have an internet connection right now. Testing testing testing this blog post. Blog posts are cool.

Published:

This is a sample blog post. Lorem ipsum I can’t remember the rest of lorem ipsum and don’t have an internet connection right now. Testing testing testing this blog post. Blog posts are cool.

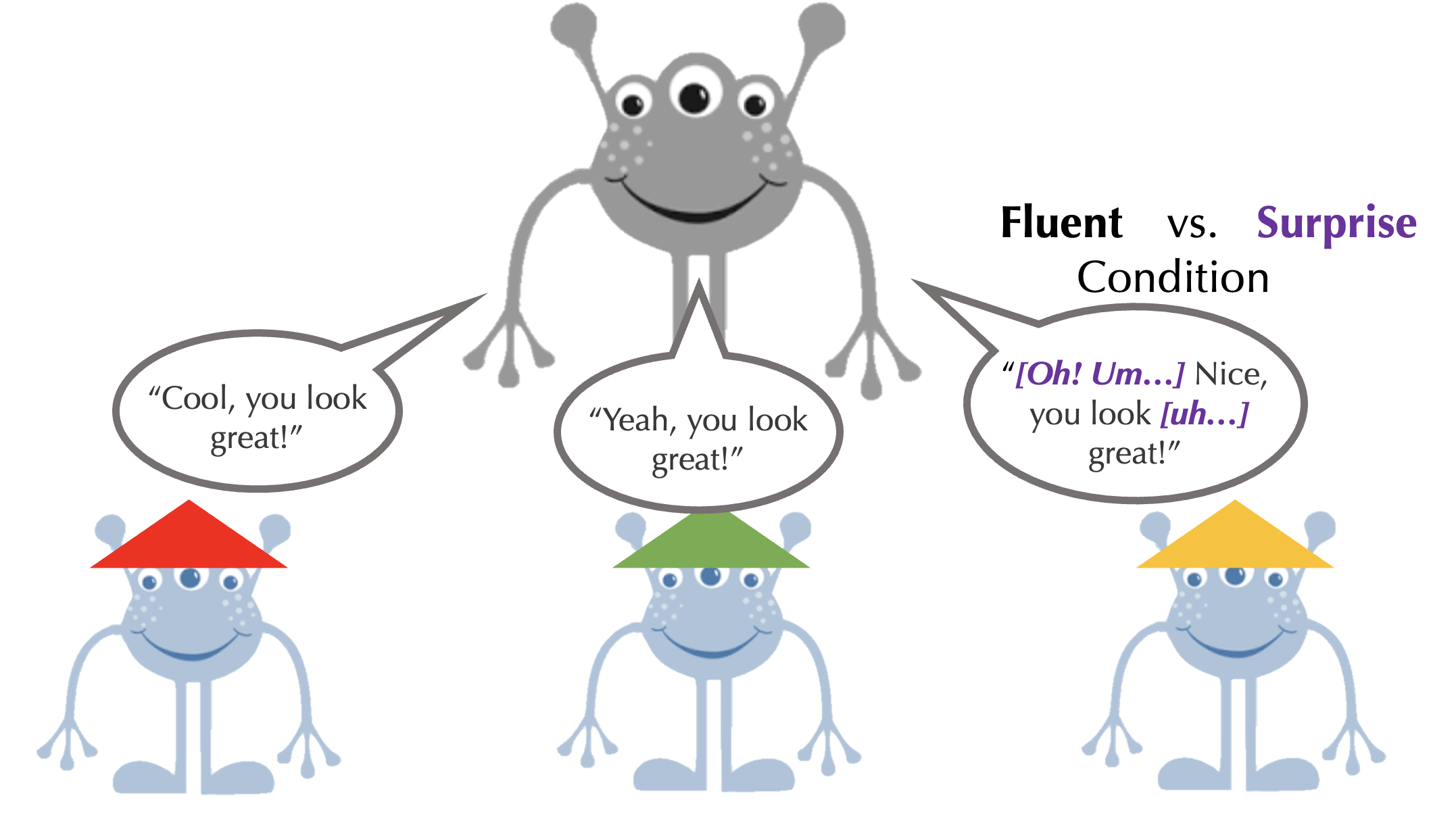

Delays and disfluencies (“um”) are ubiquitous in everyday conversation and often signal rich information about what’s going on inside a speaker’s mind. How—and how quickly—something is said can be as meaningful as what is said. In this line of work, I investigate how children (and adults) use disfluencies to infer a speaker’s underlying mental processes. My research explores how children use these cues to reason about just how much someone knows and what their true underlying feelings are. In this work, I argue that children’s reasoning about delays and disfluencies is inferential (vs. heuristic), broad (vs. limited), and flexible (vs. fixed).

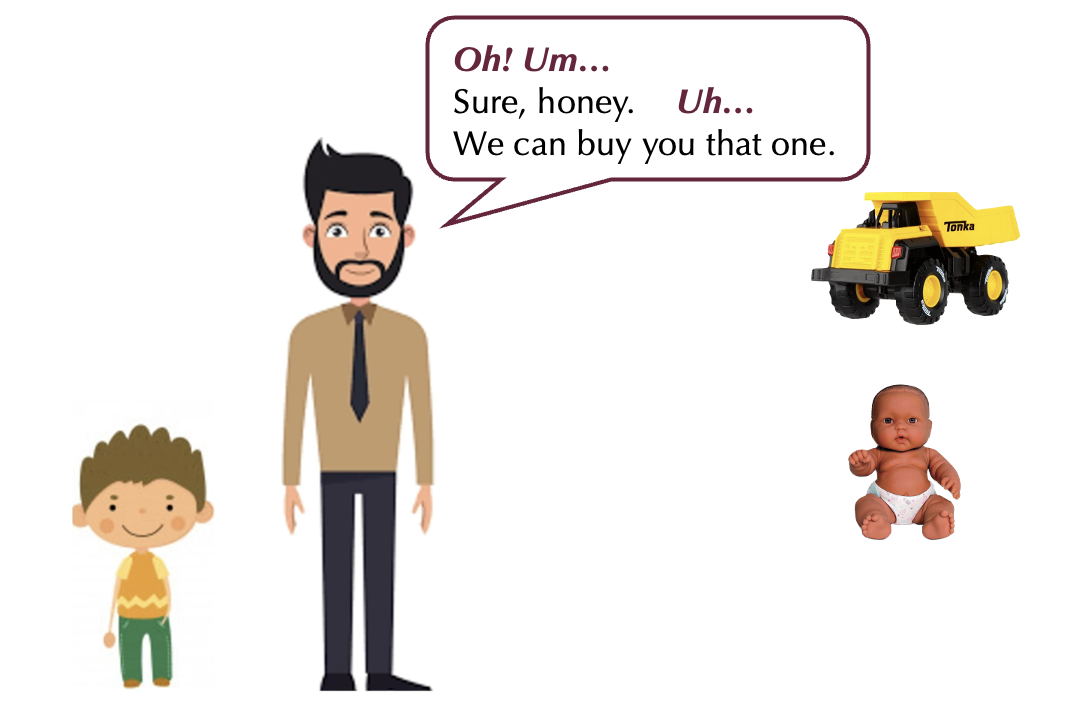

Imagine a young boy expressing a gender counter-stereotypical preference (e.g., wanting to buy a Barbie doll) and his caregiver provides a permissive, gender egalitarian response. However, imagine that response comes slowly, with markers of surprise and production difficulty (e.g., “Oh! Um. . . Sure”). What message does that young boy really receive?

Imagine a young boy expressing a gender counter-stereotypical preference (e.g., wanting to buy a Barbie doll) and his caregiver provides a permissive, gender egalitarian response. However, imagine that response comes slowly, with markers of surprise and production difficulty (e.g., “Oh! Um. . . Sure”). What message does that young boy really receive?

While people may be reluctant to explicitly state social stereotypes, their underlying beliefs nevertheless emerge through subtler conversational cues, such as surprisal reactions that reveal expectations. In this line of work, I investigate how messages that are explicitly permissive and outwardly egalitarian (e.g., “Sure, you can have that one”) might nevertheless be interpreted very differently based on presence of surprisal cues like interjections (“oh!”) and disfluencies (“um”). This work provides emerging evidence that conversational feedback may play a critical and underappreciated role in the transmission of social beliefs ( Morris & Shaw, 2024).

Published in Proceedings of the 41st Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 2019

Published in Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2020

Published in Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 2020

Published in Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 2021

Published in Proceedings of the 46th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 2024

Published:

This is a description of your talk, which is a markdown files that can be all markdown-ified like any other post. Yay markdown!

Published:

This is a description of your conference proceedings talk, note the different field in type. You can put anything in this field.

Undergraduate course, University 1, Department, 2014

This is a description of a teaching experience. You can use markdown like any other post.

Workshop, University 1, Department, 2015

This is a description of a teaching experience. You can use markdown like any other post.