How do we read minds in conversation?

At every turn in conversation, we tailor what we say (and don't say) based on what we think others know already, and adjust on the fly as we track understanding in real time. These moment-to-moment adjustments rely on rapid inferences about others’ mental states, often from fleeting, subtle cues rather than explicit signals. My research explores how people make and update these inferences with remarkably little information. I focus on how people use subtle cues (e.g., hesitation, disfluency, or shifts in tone) to infer what others know, believe, or intend. These moment-to-moment inferences don’t just support smooth interaction—they shape how we learn from others and how we learn about others.

I study this process developmentally: How do children learn to treat these conversational cues as evidence of thought? Methodologically, I rely on behavioral experiments with children and adults, corpus analysis of natural speech, and computational modeling to understand how these conversational inferences unfold and change over development. Below are some examples of my ongoing research:

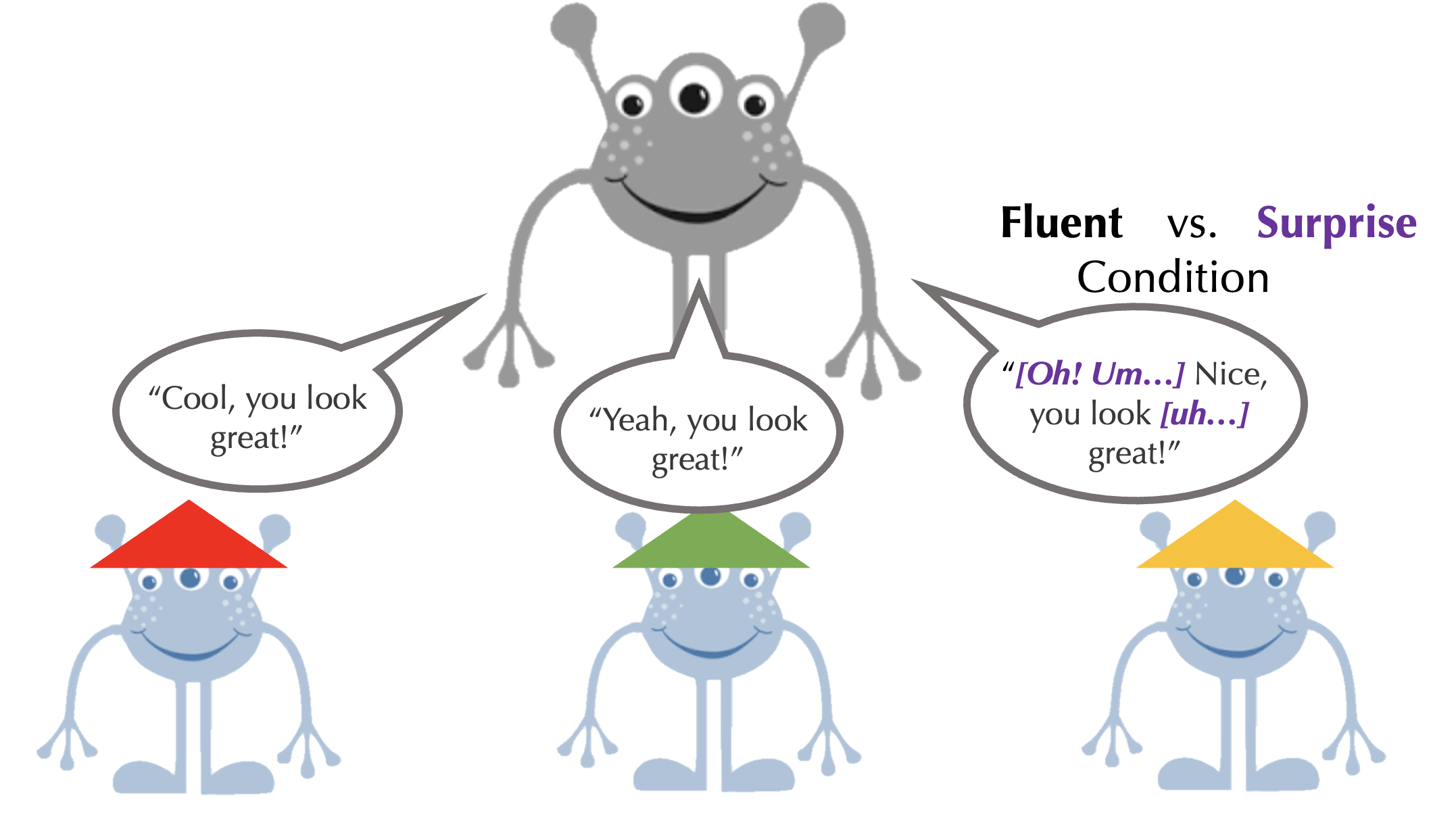

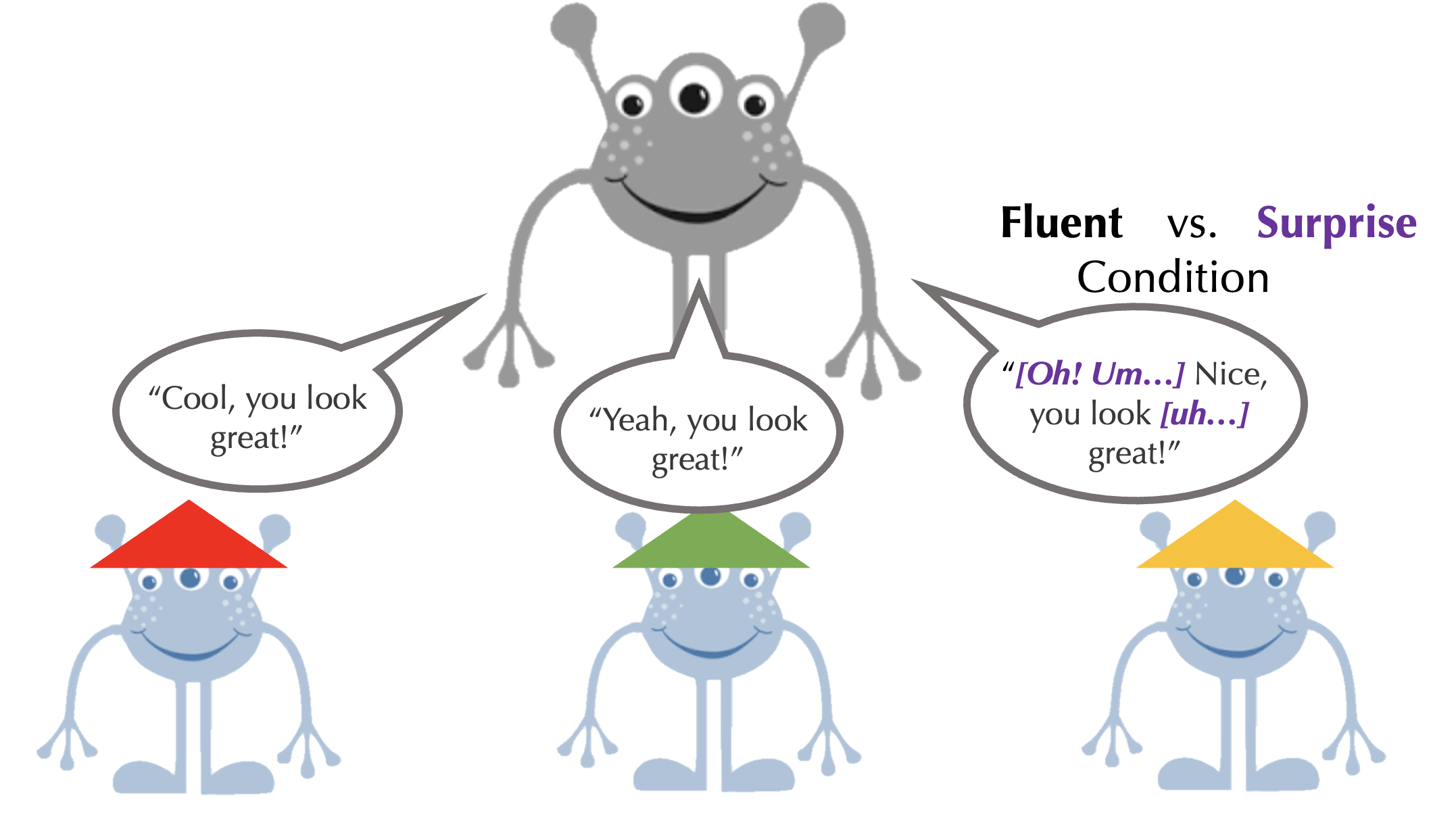

Delays and disfluencies (“um”) are ubiquitous in everyday conversation and often signal rich information about what’s going on inside a speaker’s mind. How—and how quickly—something is said can be as meaningful as what is said. In this line of work, I investigate how children (and adults) use disfluencies to infer a speaker’s underlying mental processes. My research explores how children use these cues to reason about just how much someone knows and what their true underlying feelings are. In this work, I argue that children’s reasoning about delays and disfluencies is inferential (vs. heuristic), broad (vs. limited), and flexible (vs. fixed).

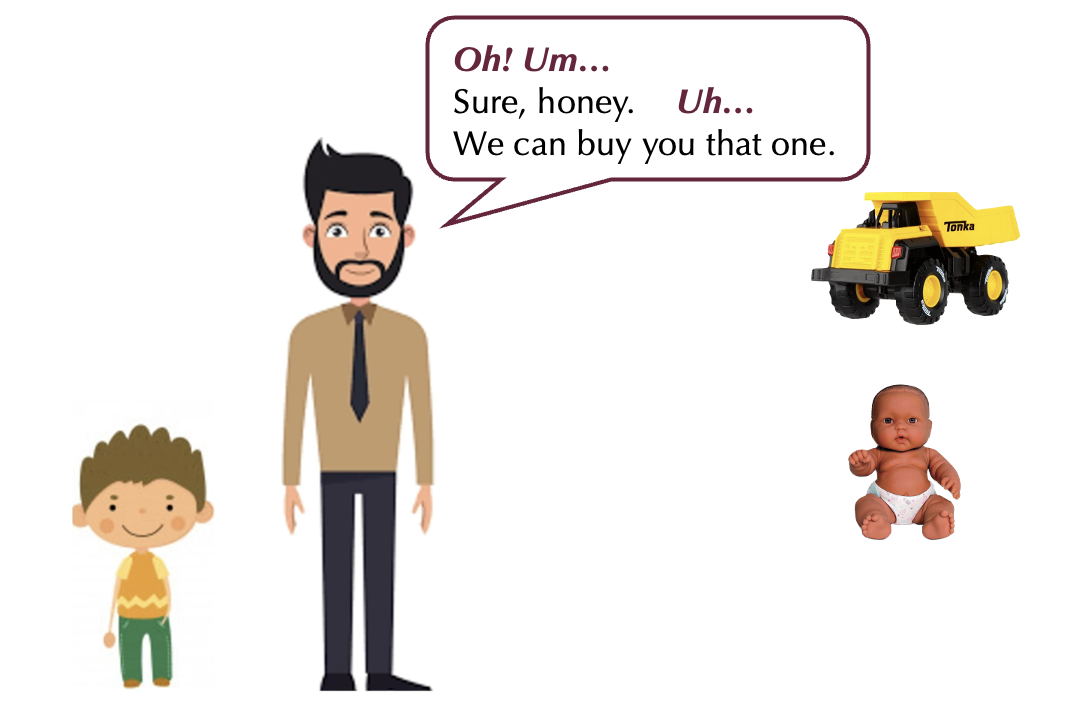

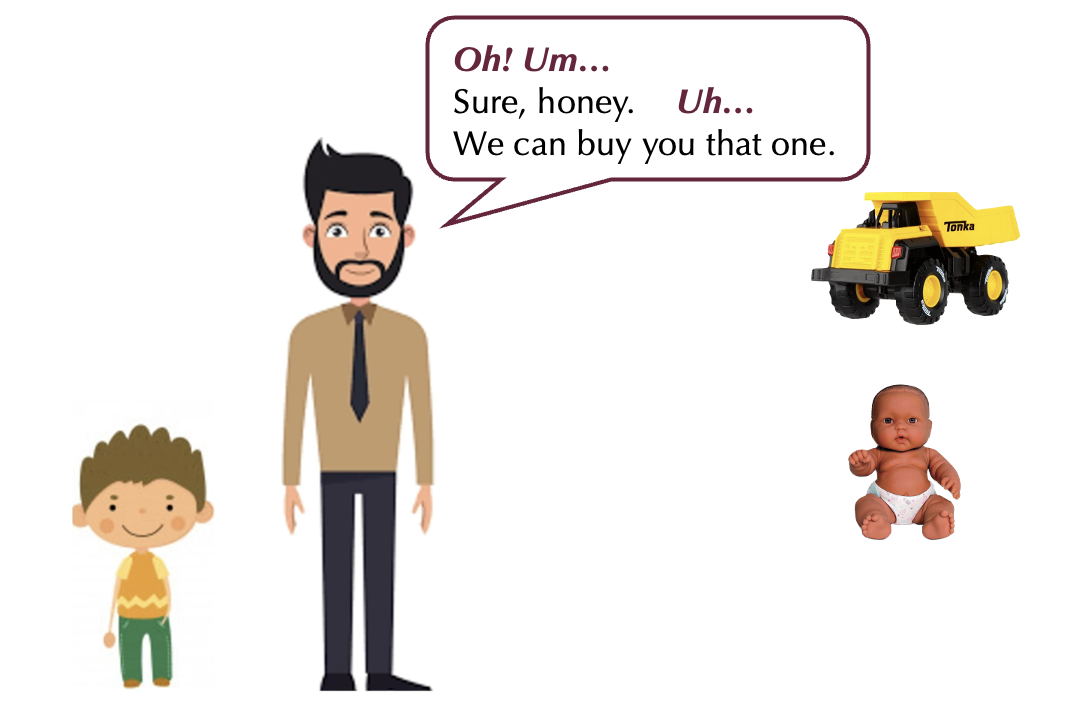

Imagine a young boy expressing a gender counter-stereotypical preference (e.g., wanting to buy a Barbie doll) and his caregiver provides a permissive, gender egalitarian response. However, imagine that response comes slowly, with markers of surprise and production difficulty (e.g., “Oh! Um. . . Sure”). What message does that young boy really receive?

Imagine a young boy expressing a gender counter-stereotypical preference (e.g., wanting to buy a Barbie doll) and his caregiver provides a permissive, gender egalitarian response. However, imagine that response comes slowly, with markers of surprise and production difficulty (e.g., “Oh! Um. . . Sure”). What message does that young boy really receive?

While people may be reluctant to explicitly state social stereotypes, their underlying beliefs nevertheless emerge through subtler conversational cues, such as surprisal reactions that reveal expectations. In this line of work, I investigate how messages that are explicitly permissive and outwardly egalitarian (e.g., “Sure, you can have that one”) might nevertheless be interpreted very differently based on presence of surprisal cues like interjections (“oh!”) and disfluencies (“um”). This work provides emerging evidence that conversational feedback may play a critical and underappreciated role in the transmission of social beliefs ( Morris & Shaw, 2024).

Imagine a young boy expressing a gender counter-stereotypical preference (e.g., wanting to buy a Barbie doll) and his caregiver provides a permissive, gender egalitarian response. However, imagine that response comes slowly, with markers of surprise and production difficulty (e.g., “Oh! Um. . . Sure”). What message does that young boy really receive?

Imagine a young boy expressing a gender counter-stereotypical preference (e.g., wanting to buy a Barbie doll) and his caregiver provides a permissive, gender egalitarian response. However, imagine that response comes slowly, with markers of surprise and production difficulty (e.g., “Oh! Um. . . Sure”). What message does that young boy really receive?